South: Antarctica, Endurance, and WWI

Sir Ernest Shackleton's South was my spontaneous "heavy reading" for this spring/summer. At times, my reaction was "What did I myself get into?" It is a long first-person narrative, stylistically tedious, and inherently repetitive--but absolutely worth the commitment.

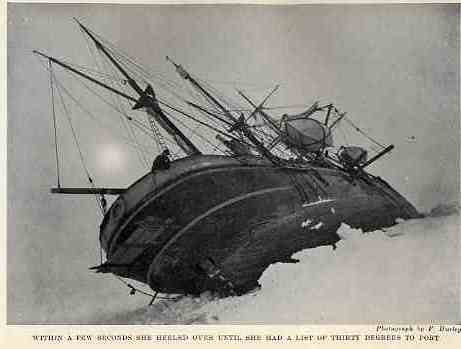

{Note: Be sure to look through photographer Frank Hurley's book South with Endurance while you read South. You will enjoy South much, much more side-by-side with the pictures. Which, by the way, are phenomenal. On top of the discomfort and anxieties of everyday survival, Hurley dedicated himself to photographing the journey, and his photos, like illustrations, truly embody the narrative/journals. A few are even in color!}

Autumn 1914. The Great War is being fought, yet as Sir Ernest Shackleton's volunteering of his expedition and resources is politely refused by the British government, he has embarked upon his planned expedition--south. He has two ships: the Endurance and the Aurora. Beginning on the Ross Sea coast, the group from the Aurora is to set up depots with supplies at key points on the Antarctic continent. From the Weddell Sea, the Endurance is to bring Shackleton to the point where he will lead the first ever crossing of the continent.

But the Endurance never makes it. The Weddell Sea proves increasingly unnavigable, until the ice begins to crush the ship slowly. Shackleton and his men have no goal left except to find a way home through minus freezing weather, with only what provisions they find or what things they can salvage from the dying Endurance. Radio signals are nonexistent, and they are left to imagine how the Aurora fared and how/whether the War had ended.

This book earns the 5 out of 5 stars. It was not a pageturner, but it was overall enthralling. As a serious survival story, it covers every small step of the voyage in great detail. Yes, it was often boring. Still, I felt a tremendous amount of respect for Shackleton's conscientious narrative, and I'm sure the public, as well as friends and family, must have appreciated his in-depth account. It also gives the reader a good sense of time/scale and immerses you in the story by not sugarcoating the reality.

Additionally, this in-depth style increased my appreciation of their perseverance through the tedium and mental fatigue, which could come all too easily. This is, after all, a huge part of what survival is about. Every day, the same food, the same monotonous jobs, the same painstaking attempts to keep clothes dry or find safe shelter. Shackleton recognized the power of morale and took it into consideration while making many decisions.

Obviously, a first-person narrative is unavoidably biased towards the author. With a grain of salt, I really admired Ernest Shackleton: he came across as what a leader and survivor should be. Circumspect, caring for his expedition members, totally self-confident and focused on his goal, not letting anxiety get the upper hand. “A man must shape himself to a new mark directly the old one goes to ground." I can imagine what he went through when he, in a sense, failed before he began, but whatever disappointment went through his mind, it didn't seem to affect his resolve.

Shackleton was tough. . .I get the impression he had high standards/expectations of people, wouldn't tolerate anything like moping around or giving up. And he lived up to his own standards (as good tough people do).

In this book, there is a little confusion at first as to "who's who"--another reason to look at the Hurley book; it explains everything and some. Shackleton was not the captain of the Endurance; the captain was Frank Worsley, a very talented, dependable guy, who went on to become a WWI hero. He wrote his own accounts of the expedition, which I hope to read in the future.

To call South an extraordinary story is an understatement. Over and over again the men are saved in the nick of time or by the most incredible circumstances (the lost/found rudder!). Shackleton openly acknowledges that God was watching out for them. Regardless of your religious beliefs, you can't help but be moved by their narrow escapes from death.

I loved the (all too-infrequent) personal side of the story--the soccer games on the ice pack, the huge importance of the portable stove, and the cookbook which both comforts and torments the half-starving men.

South reads like a very modern story, with one gigantic piece of another world: a wooden ship. They have science, and a little technology, and an increasingly 20th-century way of thinking, but there is that great, beautiful, wretched wooden ship sinking in the distance. Just seeing that and living amid 21st-century technology, I felt nearly from the beginning of South that it was a hopeless voyage from the start. How could anyone have believed that a wooden ship, steam or no steam, could live long enough through Antarctica ice?

...my mind turned to the crossing of the continent, for I was morally certain that either Amundsen or Scott would reach the Pole on our own route or a parallel one. After hearing of the Norwegian success I began to make preparations to start a last great journey—so that the first crossing of the last continent should be achieved by a British Expedition.Rings a bell? Shackleton, here and elsewhere, makes it clear that he views the expedition as almost a subcategory of WWI, indirectly related if nothing else. This, to me, is one of the greatest tragedies of the Endurance expedition. It wasn't enough to want to cross Antarctica--no, Britain must be the first. And so fifty-six men suffered hellishly for this cause.

It does not matter that it was a British expedition or that Shackleton wrote those words; the sentiment is typical of many nations' mentalities which led up to WWI. The symbolism is striking, and again, depressing. Add to that an irony: it is likely that fewer men died on the expedition than would have been the case if they instead fought side-by-side in WWI (as many of them later did).

Is nature, then--at its most extreme--a kinder opponent than our own fellow human beings?

Comments