Seven Pillars of Wisdom - 3: A Railway Diversion

Previously: Introduction, Book I, Book II

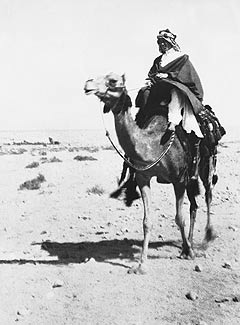

In the previous part, T. E. Lawrence acquiesced to his general's request and returned to the field, where he and Feisal took the port city of Wejh, a key victory on the western side of Arabia. For most military men, this would have been a credit to their resume, but hardly the foundation for legend. Lawrence, on the other hand, was just getting started - he was not a military man so much as he was a strategic thinker, and how he would build upon this success was, perhaps, no less important than the success itself.

Though the movie streamlines this part of the story quite a bit, in reality, a rather intricate thread of politics directed Lawrence's next movements after Wejh. Already he had his eye on Akaba, but his idea of attack - strictly from land and not sea, leading Arabs rather than French or English - was another point of contention between him and the French commander, Colonel Bremond. Additionally, the British wanted to be at Medina, a city southeast of Wejh, from which the Turks were said to be evacuating and would apparently fall easy prey. Lawrence, to be diplomatic, agreed to go to Abdulla, Feisal's older brother, and try to recruit his support for this effort.

During this journey, Lawrence contracts a bad fever, and two significant things happen during this time. First, one man in his group murders another, and Lawrence, as the only tribally neutral person, finds no ultimate alternative than to serve as the executioner. In the film, he later confesses he "enjoyed" shooting the man, but in the book, he describes the scene somberly, and with little comment, except that in the page title (there is a "summary" title for each page in the book), he calls it "Another Murder." I'm not sure he didn't think of himself as an executioner, doing what the situation called for, but his general tone implies he was bothered by it - there's certainly no suggestion he enjoyed it.

"As I have shown, I was unfortunately as much in command of the campaign as I pleased, and was untrained" (p. 193). The second thing that Lawrence did in his illness was perhaps one of the most important of his career. While lying in his tent, miserable and immobile, he reexamined the Brits' current plans more critically, using what he remembered from military books he had read in college. He concluded Medina was not the best objective, and, in general, the slower and more cumbersome European style of fighting was not going to be the Arabs' strength. They must instead work with mobility, knowledge, and calculation, using the vast and hilly terrain to their chief advantage.

During the midst of this, Lawrence was becoming even more educated in the Bedouin culture, especially since meeting Abdulla. Lawrence seemed less comfortable in Abdulla's camp than he was in Feisal's; personality-wise, they were much less alike than he and Feisal. It was also difficult for him to appreciate the older brother's hospitality - Lawrence was a self-professed loner, and, though patiently gracious, got tired of some of the highly social customs and having to live closely with others. I could write a whole post on this part, but it was just an interesting piece of the whole, and, once again, something that was not really touched upon by the film.

In the end, his better judgment could not confine himself to the "official" plan of taking Medina. So, with "a letter full of apologies" (p. 233) to General Clayton, Lawrence returned to his former scheme of focusing the attack on Akaba, and set off on his own initiative to make it happen.

|

| My |

In the previous part, T. E. Lawrence acquiesced to his general's request and returned to the field, where he and Feisal took the port city of Wejh, a key victory on the western side of Arabia. For most military men, this would have been a credit to their resume, but hardly the foundation for legend. Lawrence, on the other hand, was just getting started - he was not a military man so much as he was a strategic thinker, and how he would build upon this success was, perhaps, no less important than the success itself.

Though the movie streamlines this part of the story quite a bit, in reality, a rather intricate thread of politics directed Lawrence's next movements after Wejh. Already he had his eye on Akaba, but his idea of attack - strictly from land and not sea, leading Arabs rather than French or English - was another point of contention between him and the French commander, Colonel Bremond. Additionally, the British wanted to be at Medina, a city southeast of Wejh, from which the Turks were said to be evacuating and would apparently fall easy prey. Lawrence, to be diplomatic, agreed to go to Abdulla, Feisal's older brother, and try to recruit his support for this effort.

During this journey, Lawrence contracts a bad fever, and two significant things happen during this time. First, one man in his group murders another, and Lawrence, as the only tribally neutral person, finds no ultimate alternative than to serve as the executioner. In the film, he later confesses he "enjoyed" shooting the man, but in the book, he describes the scene somberly, and with little comment, except that in the page title (there is a "summary" title for each page in the book), he calls it "Another Murder." I'm not sure he didn't think of himself as an executioner, doing what the situation called for, but his general tone implies he was bothered by it - there's certainly no suggestion he enjoyed it.

"As I have shown, I was unfortunately as much in command of the campaign as I pleased, and was untrained" (p. 193). The second thing that Lawrence did in his illness was perhaps one of the most important of his career. While lying in his tent, miserable and immobile, he reexamined the Brits' current plans more critically, using what he remembered from military books he had read in college. He concluded Medina was not the best objective, and, in general, the slower and more cumbersome European style of fighting was not going to be the Arabs' strength. They must instead work with mobility, knowledge, and calculation, using the vast and hilly terrain to their chief advantage.

In Turkey things were scarce and precious, men less esteemed than equipment... Ours should be a war of detachment. We were to contain the enemy by the silent threat of a vast unknown desert, not disclosing ourselves till we attacked. The attack might be nominal, directed not against him, but against his stuff... (p. 199, 200)This was the light-bulb moment that started his campaign to dismantle the Turkish railways. He started work upon this soon afterwards, intent upon striking the Turks by taking away their resources, while attempting always to preserve Arab lives.

During the midst of this, Lawrence was becoming even more educated in the Bedouin culture, especially since meeting Abdulla. Lawrence seemed less comfortable in Abdulla's camp than he was in Feisal's; personality-wise, they were much less alike than he and Feisal. It was also difficult for him to appreciate the older brother's hospitality - Lawrence was a self-professed loner, and, though patiently gracious, got tired of some of the highly social customs and having to live closely with others. I could write a whole post on this part, but it was just an interesting piece of the whole, and, once again, something that was not really touched upon by the film.

In the end, his better judgment could not confine himself to the "official" plan of taking Medina. So, with "a letter full of apologies" (p. 233) to General Clayton, Lawrence returned to his former scheme of focusing the attack on Akaba, and set off on his own initiative to make it happen.

Comments