"...he might be understood; but not today."

|

| T. E. Lawrence (1888–1935) |

If you've been following me on Goodreads, you'll understand I have been reading books this year, while blogging at a record low. Far from a lack of interest in blogging, my motivation was the need to take a break...I still consider myself on break as I write this. However, I wanted to say a few thoughts on my longest read of the year (thus far) before removing all my markers in it and packing it off back to the library.

A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T. E. Lawrence was written by psychiatrist John E. Mack, published in 1976, and came highly rated (based on my internet research). Let me take a moment to dissect that sentence:

- First off, I felt uncomfortable with the title. The quote is not by Lawrence, and while it's provocative, I had no idea going into the book what the "disorder" refers to. What a great and awful title for a biography.

- The author is not a historian by profession, but a different type of social scientist, a psychiatrist. Interesting. What compels a psychiatrist to write a chunky (400+ p.) biography on a war hero? And what kind of research would that look like?

- Finally, what further excited me about this book was the publication date. I have a stubborn mistrust of historical books written long after the events, and this is in part stems from my negative reading experiences. One thing that can soften my bias is the timing. If the author, like Mack, has access to eye witnesses, then it obviously hasn't been written "long after" - maybe the timing is just right.

If there is a recurrent fault in the book, it is that Mack assumes you have some surface knowledge of T. E already. He probably assumes you've watched Lawrence of Arabia, and/or read encyclopedia articles. Occasionally he will throw out names and places that require that cursory knowledge to appreciate his references. I think it helps to have first read Seven Pillars of Wisdom - Lawrence's literary war memoir. If you're looking for a detailed historical account of the Arab Revolt, you would do well to start there (or even Wikipedia). Mack follows Lawrence's life, but does not attempt to spell out each of his movements in detail.

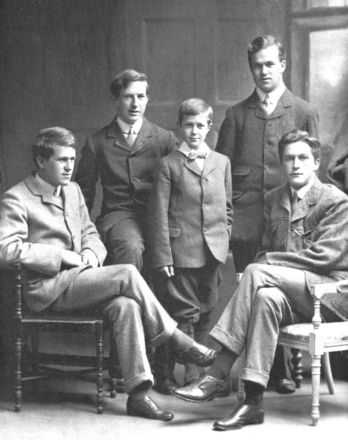

|

| The Lawrence brothers in 1910. From left to right: T. E. Lawrence (Ned), Frank, Arnold, Bob and Will. |

What you get instead - and what is more valuable in the long run - is an in-depth analysis of Lawrence the human being. Starting with his father's background, and infidelity, the story moves at a rapid pace through Thomas Edward Lawrence's development. It homes in specifically on the influences, choices, and consequences that led him one step nearer to becoming the person that he became, both in his fame and in his hidden life. I call it a "story" because it reads like one. Mack writes with refreshing simplicity, covers sensational aspects with clinical calm, and in the end paints a Dickensian-like saga of a very complicated individual. He's actually respectful of the subject, and I love that. Yet, like a doctor, he is unafraid of examining unbeautiful truths.

'...I'm always afraid of being hurt: and to me, while I live, the force of that night will lie in the agony which broke me, and made me surrender. It's the individual view. You can't share it.' (p. 419)Mack contrasts the many sides of T. E. Lawrence, which are as varied as the man's real-world pseudonyms. He draws on Lawrence's memoirs, letters, and living acquaintances as the bulk of his supporting evidence for his theme: that Lawrence's personal life had significant bearing upon his political life, and that through this twist, he became a uniquely 20th-century hero - perhaps the first.

|

| Lawrence on his Brough Superior |

The phrase "a prince of our disorder" originates from Irving Howe, a literary and social critic. This "disorder" relates to the conflict of interest that Lawrence epitomized, both as an exemplary British officer and as a proponent for Arab autonomy. Mack explores the idea that Lawrence changed Western culture's conception of a hero. No longer was a heroic figure simply a war machine and conqueror who was "always right" - a dubious Zeus if you will, or the knights and Crusaders which fascinated Lawrence in his youth. Rather, a modern hero evolved, through Lawrence and WWI, into a moral hero.

Lawrence, though a soldier and a hero of war, is also a hero of nonwar. By the assumption of exaggerated personal responsibility for what war really is, he has demonstrated war's unsuitability as material for heroism according to the twentieth-century consciousness he helped to create...He asks us to expect more of our heroes as he expected more of himself, and we are influenced thereby to be more self-critical and to demand more of our leaders. (p. 219)The movie is still, in my opinion, an incredible one; it shows something of this battle between legend versus reality. And yet, you get less than half the picture when you just see "Lawrence the Legend." The legend doesn't tell you he buried himself in the Middle East after being rejected by Janet Laurie. It doesn't tell you he got, in the Revolt, what he'd long dreamed for, and it just about killed him. It doesn't tell you he worked himself to misery in the Paris peace talks, and it ignores or glosses over his post-War trauma. Finally, the legend doesn't even give a hint of the penitence and charitable works he sought in the late '20s and early '30s.

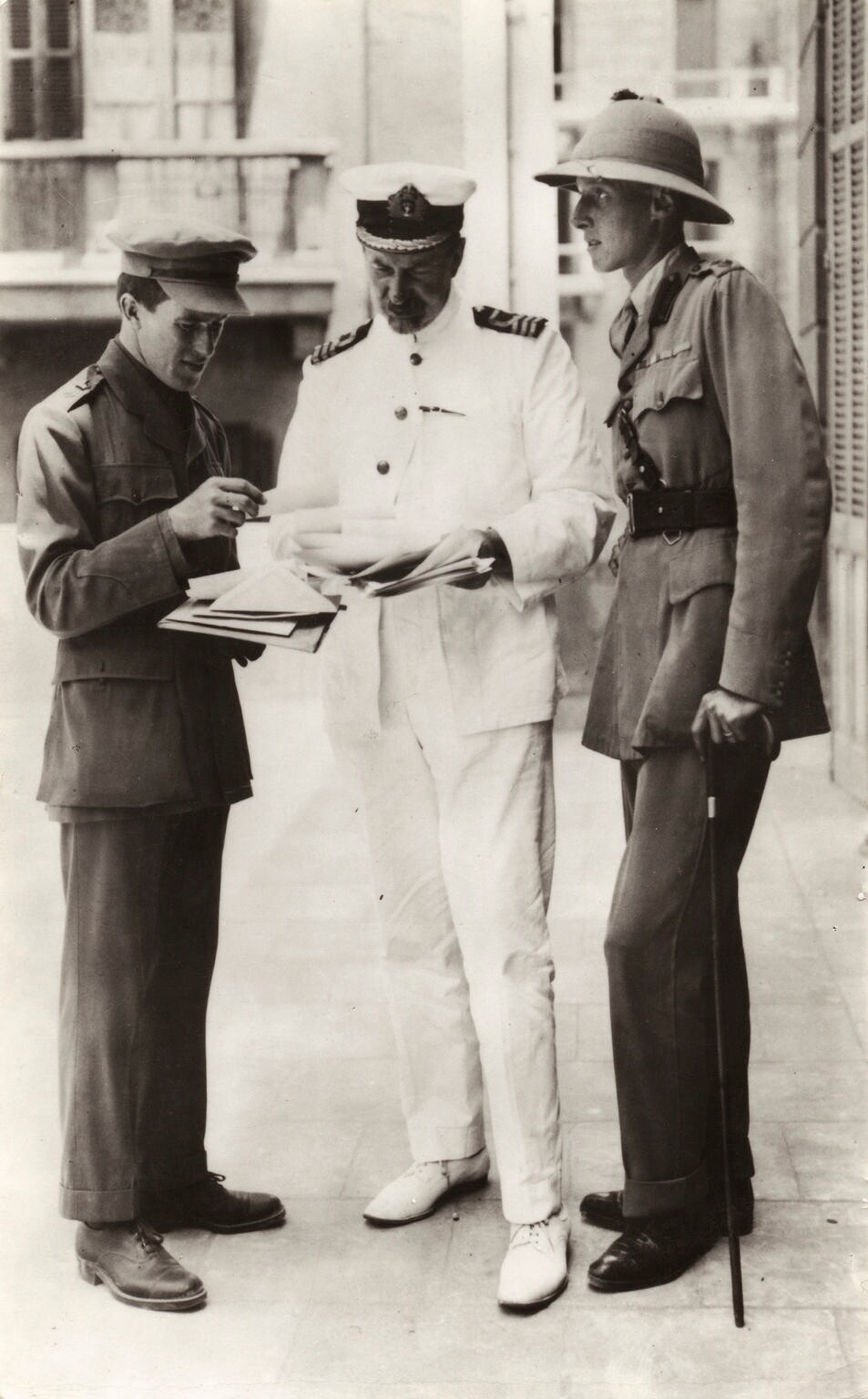

|

| Lt-Col Thomas Edward Lawrence, D.G. Hogarth, and Lt-Col Dawnay, at the Arab Bureau of Britain's Foreign Office, Cairo, May 1918. |

His friend and ally, Faisal, summed this up well: "...a genius, of course, but not for this age... A hundred years hence, perhaps two hundred years hence, he might be understood; but not today." (p. 204)

Comments