Seven Pillars of Wisdom - 5 & 6: Marking Time; The Raid upon the Bridges

Previously: Introduction, Book I, Book II, Book III, Book IV

After the capture of Akaba, the Arab Revolt was again able to re-focus on its core strategy: destroying the Turkish railway in Hejaz. This followed Lawrence's philosophy of undermining Turkish resources instead of targeting their forces directly, following the priority of utilizing the Arab advantage - mobility and knowledge of terrain - and preserving Arab lives.

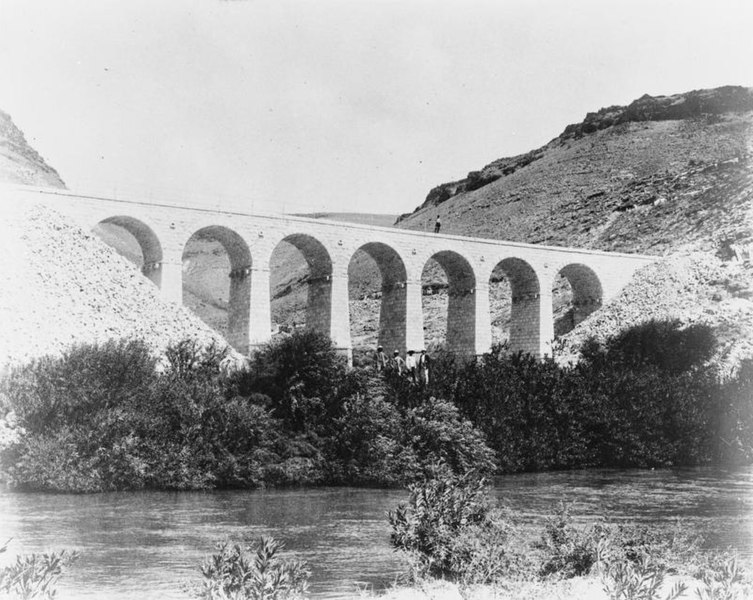

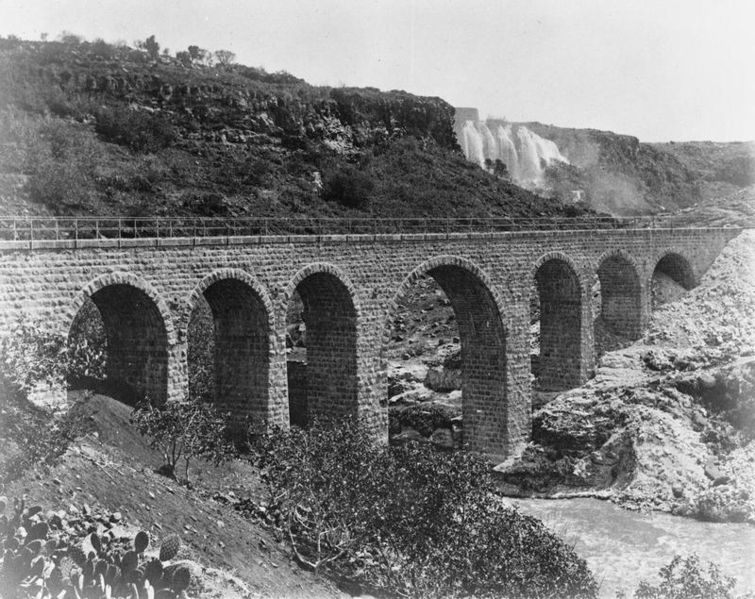

With the help of British expertise and the leadership of Arab sherifs, Lawrence set this plan into reality, both leading and training the Arab fighters in a series of bomb attacks on the railway. The most materially valuable points were the stations, full of loot for the men to take back to their tribes...the most vulnerable points were the bridges.

These two parts were rich with Lawrence's insights on not only his own actions, thoughts, and struggles during this time, but also the geographical features he saw, the behavior and attitudes of other British officers (and the British Empire in general), and the behavior and attitudes of the Arab tribes and their leaders. He wrote an entire section upon "Syria in 1915" - could he have known that so much of it is still relevant 100 years later? His remarks on Western intervention in Middle Eastern politics are candid, self-reviling, and far from outdated. It is both depressing and fascinating, one of the best parts in the entire book.

At the end of book 6, Lawrence goes to the town of Deraa to investigate its layout prior to an attack. Something that had confused me in the film was his confidence that he could pass for Arab, yet in the book this is supported, in several places, by instances when he successfully disguised himself, at least from a distance. He succeeds in Deraa, but is apprehended by the Turks and conscripted into the infantry.

The film shows nothing as disturbing as what Lawrence describes. The Turkish soldiers take him to the Bey (governor), who, in his position of power, satisfies his lusts using the most attractive officers. He tries to rape Lawrence, and when Lawrence defends himself, the Bey orders him to be beaten. The horrific flogging leaves him undesirable to the Bey, and he is finally released and sent to the soldiers' quarters.

There he finds a suicide drug from the dispensary, takes it with him in case of recapture, and escapes without notice. But the physical torture by the Turks becomes linked with his mental torture of guilt, and he writes that from that point "the citadel of my integrity had been irrevocably lost" (p. 456).

After the capture of Akaba, the Arab Revolt was again able to re-focus on its core strategy: destroying the Turkish railway in Hejaz. This followed Lawrence's philosophy of undermining Turkish resources instead of targeting their forces directly, following the priority of utilizing the Arab advantage - mobility and knowledge of terrain - and preserving Arab lives.

|

| The Hejaz Railway, 1908 |

With the help of British expertise and the leadership of Arab sherifs, Lawrence set this plan into reality, both leading and training the Arab fighters in a series of bomb attacks on the railway. The most materially valuable points were the stations, full of loot for the men to take back to their tribes...the most vulnerable points were the bridges.

These two parts were rich with Lawrence's insights on not only his own actions, thoughts, and struggles during this time, but also the geographical features he saw, the behavior and attitudes of other British officers (and the British Empire in general), and the behavior and attitudes of the Arab tribes and their leaders. He wrote an entire section upon "Syria in 1915" - could he have known that so much of it is still relevant 100 years later? His remarks on Western intervention in Middle Eastern politics are candid, self-reviling, and far from outdated. It is both depressing and fascinating, one of the best parts in the entire book.

Arab Government in Syria, though buttressed on Arabic prejudices, would be as much 'imposed' as the Turkish Government, or a foreign protectorate, or the historic Caliphate. Syria remained a vividly coloured racial and religious mosaic. Any wide attempt after unity would make a patched and parcelled thing, ungrateful to a people whose instincts ever returned towards parochial home rule. (p. 344–345)As I sit here, the West is still trying to "stabilize" the Middle East and still experiencing - yet hardly learning? - the lessons of a century ago. Lawrence could have told us what to expect.

The fraudulence of my business stung me. Here were more fruits, bitter fruits, of my decision, in front of Akaba, to become a principal of the Revolt. I was raising the Arabs on false pretences, and exercising a false authority over my dupes... In such conditions the war seemed as great a folly as my sham leadership a crime... (p. 387)It always came back to the War. The War was Lawrence's one justification, and even that at times left him cold and cynical of its priority, which was one of the elements - though perhaps not the only one - that set his conscience in a cruel balance. Was he British first, or was he his own, undefinable self above all? Were his actions reestablishing his character in a way he did not like or want?

There were Englishmen whom, individually, the Arabs preferred to any Turk, or foreigner; but, on the strength of this, to have generalized and called the Arabs pro-English, would have been a folly. Each stranger made his own poor bed among them.Though fluent in Arabic and living nearly as one of them, he still felt like a stranger.

At the end of book 6, Lawrence goes to the town of Deraa to investigate its layout prior to an attack. Something that had confused me in the film was his confidence that he could pass for Arab, yet in the book this is supported, in several places, by instances when he successfully disguised himself, at least from a distance. He succeeds in Deraa, but is apprehended by the Turks and conscripted into the infantry.

The film shows nothing as disturbing as what Lawrence describes. The Turkish soldiers take him to the Bey (governor), who, in his position of power, satisfies his lusts using the most attractive officers. He tries to rape Lawrence, and when Lawrence defends himself, the Bey orders him to be beaten. The horrific flogging leaves him undesirable to the Bey, and he is finally released and sent to the soldiers' quarters.

There he finds a suicide drug from the dispensary, takes it with him in case of recapture, and escapes without notice. But the physical torture by the Turks becomes linked with his mental torture of guilt, and he writes that from that point "the citadel of my integrity had been irrevocably lost" (p. 456).

Comments