The Divine Comedy - Part 1: Inferno

Dante, lost in a dark forest, is overcome by feelings of fear and loneliness, until he is met by the spirit of Virgil, the Roman poet and author of the Aeneid. Virgil was sent by Beatrice, Dante's deceased childhood sweetheart, to come to his aid and help him back into the way of light and salvation. The way back, however, starts as a downward descent into and through the nine circles of Inferno. The journey becomes a test to Dante's courage as he, led on by Virgil, faces the cries, tortures, and apparitions of sufferers in Hell, some of whom he recognizes.

As I write this, Christmas is just four days away, which may be why I could not help thinking of A Christmas Carol when I read this: Virgil as a more kindly Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, and Dante as a melancholy Scrooge. However, Tolkien also came to mind, for Inferno is as terrifying a landscape as Mordor (perhaps moreso), filled with graphic portrayals of misery and torment. Virgil then leads as a stern elf or wizard, and Dante is our hobbit. The half-dead prisoners of Inferno are like so many Gollums - half-despicable, half-pitiable in their anguish and hatred.

There are many, many references to contemporary and historical figures in this story, and most of them are Italian. I chose not to read an annotated edition (feeling I would never make it through) but instead looked up names along the way when the context was insufficient. The edition I read was the Henry Longfellow translation, with summaries of each canto by Anna Amari-Parker. Apart from one or two confusing ones, I felt the summaries greatly helped my understanding of the text.

To be perfectly honest, I was underwhelmed by the story itself. While initially the trek through monsters and chasms draws you in, it seemed to grow quickly repetitive. As he descends from circle to circle, Dante finds different groups of people being tortured in different ways; he frequently stops to talk to people he recognizes and is chastised by Virgil if he lingers too long. Virgil, elf-like, saves him from any real danger by finding "the way out" or by flight if necessary. And so it goes on, till they reach the last scene of despair.

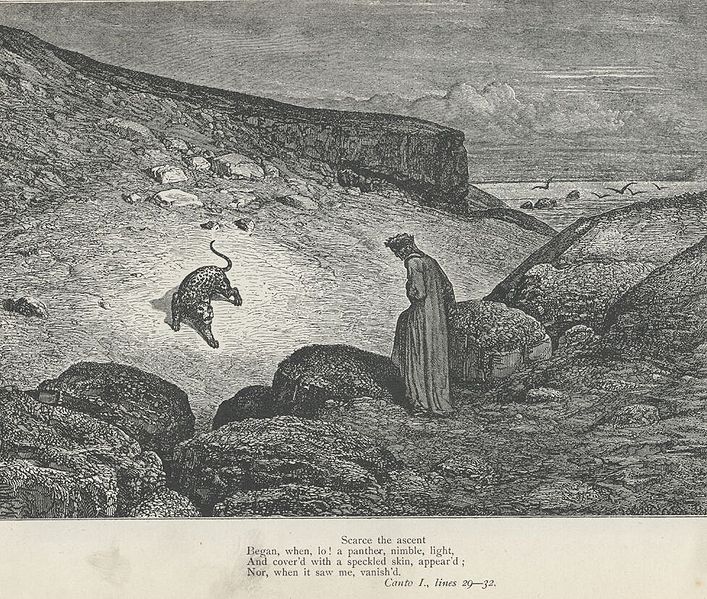

What really made the book stand out to me were the illustrations by Gustave Doré. In total, he created 135 wood-engraved illustrations for The Divine Comedy, which, in Inferno, average to 2-3 full illustrations per canto! Keep in mind, Inferno contains mostly pictures of the cloaked Virgil and Dante staring at crowds of writhing, very nude figures, not a pleasant subject. In context, however, it's effective as an almost graphic-novel style of storytelling. Doré also excels at atmospheric landscape and lighting, making you sometimes forget you're looking at a wood engraving. Not gonna lie, I preferred the illustrations over the writing.

This one is my favorite, which I used before in my review of The Brothers Karamazov. These are the traitors trapped in ice, and you can hardly believe what skill it takes to portray ice in wood, yet he does, brilliantly:

Being as enamored of wood engravings as I am, I did some searching to see how it's actually done. I found a demo by an artist named Anne Desmet, from the Royal Academy of Arts:

As I write this, Christmas is just four days away, which may be why I could not help thinking of A Christmas Carol when I read this: Virgil as a more kindly Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, and Dante as a melancholy Scrooge. However, Tolkien also came to mind, for Inferno is as terrifying a landscape as Mordor (perhaps moreso), filled with graphic portrayals of misery and torment. Virgil then leads as a stern elf or wizard, and Dante is our hobbit. The half-dead prisoners of Inferno are like so many Gollums - half-despicable, half-pitiable in their anguish and hatred.

There are many, many references to contemporary and historical figures in this story, and most of them are Italian. I chose not to read an annotated edition (feeling I would never make it through) but instead looked up names along the way when the context was insufficient. The edition I read was the Henry Longfellow translation, with summaries of each canto by Anna Amari-Parker. Apart from one or two confusing ones, I felt the summaries greatly helped my understanding of the text.

To be perfectly honest, I was underwhelmed by the story itself. While initially the trek through monsters and chasms draws you in, it seemed to grow quickly repetitive. As he descends from circle to circle, Dante finds different groups of people being tortured in different ways; he frequently stops to talk to people he recognizes and is chastised by Virgil if he lingers too long. Virgil, elf-like, saves him from any real danger by finding "the way out" or by flight if necessary. And so it goes on, till they reach the last scene of despair.

What really made the book stand out to me were the illustrations by Gustave Doré. In total, he created 135 wood-engraved illustrations for The Divine Comedy, which, in Inferno, average to 2-3 full illustrations per canto! Keep in mind, Inferno contains mostly pictures of the cloaked Virgil and Dante staring at crowds of writhing, very nude figures, not a pleasant subject. In context, however, it's effective as an almost graphic-novel style of storytelling. Doré also excels at atmospheric landscape and lighting, making you sometimes forget you're looking at a wood engraving. Not gonna lie, I preferred the illustrations over the writing.

This one is my favorite, which I used before in my review of The Brothers Karamazov. These are the traitors trapped in ice, and you can hardly believe what skill it takes to portray ice in wood, yet he does, brilliantly:

Being as enamored of wood engravings as I am, I did some searching to see how it's actually done. I found a demo by an artist named Anne Desmet, from the Royal Academy of Arts:

Comments