Ben-Hur - A Book Journal

|

| Panorama Jerusalem in Altotting by Gebhard Fugel [GFDL or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0] |

Oppressed by its own government, your native city is at the edge of a crisis. The conquering war-spirit of Mars has found its next generation of followers, and the subjugated people feel it.

Till now, your family has always managed to be safe from the conflict. Your father's prosperous work had earned the approval of the supreme leader and left you a fortune, as well as security. Your future seems certain.

Then, one day, an accident scars you with a terrible accusation. Everything changes suddenly, under the power of an angry mob and betrayal by your closest friend.

|

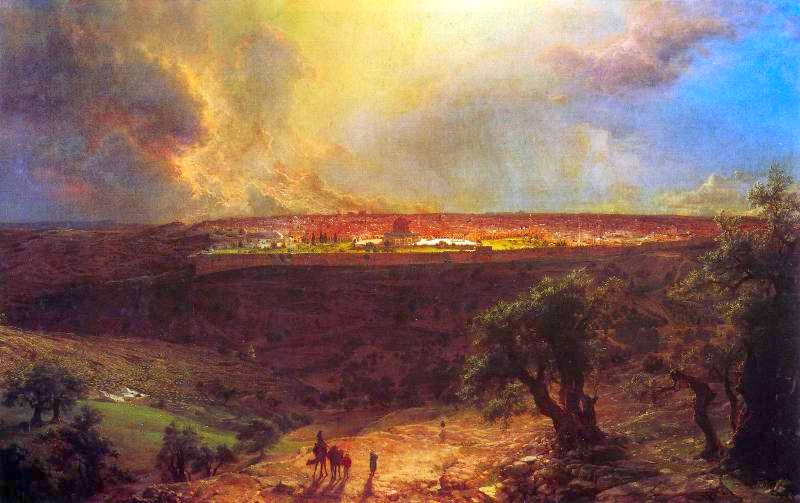

| Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives by Frederick Edwin Church |

While going over the beginning of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, I was trying to think about the 19th-century reader and what their perspective might have been. This is my second time reading the book, so personally I have a little bit of vague memory to go by, as well as the movie (ever ingrained in my consciousness) and the Focus on the Family radio drama (an excellent adaptation from what I recall). Knowing what follows in the plot, I've realized that Ben-Hur is a story for all times, which is why our ancestors loved it - it was a bestseller for decades. They were not accustomed to the cinematic format which has us spoiled today, and though I'm partial to the Charlton Heston film, I see the descriptions in the book would not be lost on the original readers. I am sure, however, they stayed for the story.

This story remains relevant, in spite of its now-lesser literary prestige than, say, Moby-Dick. Case in point: I've been reading The Accusation: Forbidden Stories from Inside North Korea, which is a collection of short stories written by a North Korean writer under the name "Bandi." So far, the common theme is that even a family with strong (Communist) Party ties is not safe from the suspicions, or retaliation, of the government. It's no perfect analogy, of course - the Hur family is not Roman or even politically aligned with them, and I am not sure if the Roman Empire was as brutal as some modern regimes. Still, the themes of fear, paranoia, injustice, and familial love are as present today as they are in Ben-Hur; humans don't really change.

I've read the first two parts of Ben-Hur and found there was more to talk about than I can describe here succinctly. So, consider this an introductory post, and I'll leave you with this quote. This is from a scene where Judah's mother attempts to undo the verbal damage done by Messala, his former friend.

Youth is but the painted shell within which, continually growing, lives that wondrous thing the spirit of man, biding its moment of apparition, earlier in some than in others. She trembled under a perception that this might be the supreme moment come to him; that as children at birth reach out their untried hands grasping for shadows, and crying the while, so his spirit might, in temporary blindness, be struggling to take hold of its impalpable future. They to whom a boy comes asking, Who am I, and what am I to be? have need of ever so much care. Each word in answer may prove to the after-life what each finger-touch of the artist is to the clay he is modelling.

Comments