Crusader Castles - A Young Lawrence of Arabia

Having resolved to read everything written by T. E. Lawrence, I inevitably picked up his college thesis, published posthumously under the title Crusader Castles.

It's a very rare book, but happily a New Year's discount made the Folio Society edition a good option, and I couldn't have been more pleased with the customer service, shipping, and, of course, the edition itself. The FS release is a reprint of the original two-volume edition, and it includes an excellent introduction by biographer Mark Bostridge, whose interest in WWI history makes it a worthy addition.

Through the introduction, you learn that T. E. Lawrence completed his thesis just four years before the outbreak of WWI. For his research, he had already traveled extensively in Britain and France, and even to Syria and Palestine - his first exposure to the Middle East and its climate, both in a geographical and political sense.

His topic? In his own words, he set out to prove "The Influence of the Crusades on European Military Architecture to the end of the Twelfth Century." In what became his trademark style, Lawrence was not afraid to take on an opposing viewpoint, even if it meant going against Sir Charles Oman, the Oxfordian expert on the subject at the time, whose own stance was that East had influenced West, not vice-versa. Lawrence, not without basis, was confident he could out-research Oman and convince his examiners that the Crusaders took their own architecture to the Holy Land.

Violently controversial points are usually settled by a plain assertion, for simplicity and peace. If they are of importance in my argument they may be discussed.It takes a geek to know one, and certainly, readers without prior knowledge of "Ned" will find this book too niche to appreciate. For fans, Crusader Castles is a gold mine of insights on his young adulthood, both in terms of personal development and in his relationships to his mentors, his family, and the world at large.

T. E.'s taste for physical exertion and adventure is well known; what is more interesting here is his capacity for organization and process. The book is filled with sketches and photographs of the castles he visits; touristy postcards were, as he points out, not capable of doing justice to the edifices. Beyond what mere observation would reveal, his drawings of castles plans show an incredible attention to scale and detail, labelled carefully and referred to in his writing with the same exactness that a mathematician might use with a graph. T. E. clearly put the science into "social science," and his commentary on crusader strategy not only points to his own extensive reading, but also to the systematic workings of his mind, which played not a small role in the Arab Revolt.

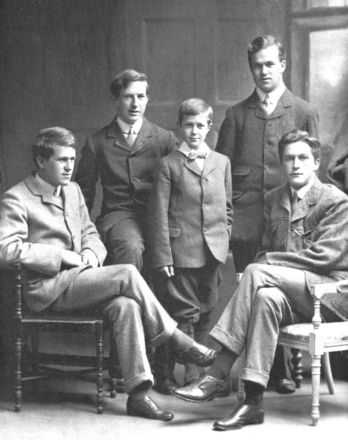

|

| Lawrence (left) and his brothers, around the time he finished Crusader Castles. |

What I enjoyed most about Crusader Castles was the personal side. Luckily for us, T. E. later added margin notes to his paper, a sort of "Older Ned Reacts to Younger Ned" commentary. His notes are two-fold: they critique his youthful research and writing style, while adding insights he gained from further thought or experience. More than that, they showcase his sense of humor, from schoolboyish remarks on "admirable latrines" to gleeful tut-tuts on his college-aged criticisms of other writers. Even within the original paper, there are delightful references to his castle climbing and (irresistibly) an encounter with a nest of snakes.

That Ned heartily enjoyed himself is no secret. The second half of the book contains a selection of letters he wrote to his family while he was abroad. Each one is fairly technical for a personal letter, suggesting he relied on his mother's care of them to supplement his notes later. A handful of these letters come from his time in the Middle East, and here we see the very first glimpse of the legendary Lawrence. It was still an innocent time in his life, when being shot at by a local was a great adventure, and that joy of exploration could not have been a small reason he soon returned to Syria as an archeologist.

Of all the book, maybe my favorite part was his letter from Aigues-Mortes, a medieval castle-city in the south of France. It is the oddity in the volume, because it is an emotional letter, in which Ned's enthusiasm for his trip and his research cannot be subdued. He quotes Blake and Shelley, letting his love of poetry show through, and in a glimpse, we see the same passion for landscape that colored his description of Wadi Rum in Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

You are all wrong, Mother dear, a mountain may be a great thing, a grand thing, but it is better to be peaceful, and quiet, and pure, omnia pacata posse mente tueri, if that is the best state, then a plain is the best country: the purifying influence is the paramount one in a plain, there one can sit down quietly and think of anything, or nothing which Wordsworth says is best, one feels the littleness of things, of details, and the great and unbroken level of peacefulness of the whole: no, give me a level plain, extending as far as the eye can reach, and there I have enough of beauty to satisfy me, and tranquility as well!

Comments